Photo credit: Andrew Bain/Creative Commons

The first time I visited a courthouse for research, I had no idea what to expect and prior to arrival was quite intimidated. I quickly found that finding your way around is usually very straightforward and using the records is fairly consistent from locality to locality. Since some of the most valuable genealogical information available is sitting - in many cases undigitized - in courthouses, it is worth pushing through the fear factor.

In this post I will walk through the steps of what to expect when visiting a courthouse from getting there to finding your documents. In this case, I was specifically looking for wills, but they are only one type of record housed in courthouses. Birth records, death records, deeds, court cases, and more are also available in courthouses. If you are lucky enough to live where you are researching, you will find yourself going back again and again. For those of us that live far from the location of our ancestors, finding a way to visit the courthouse is balanced with availing ourselves of the digitized records that are increasingly found online.

Before Heading Out: Preparation

Before I head to a courthouse, I verify what is housed there. Sometimes the county has an excellent website that offers helpful information for genealogists, other times information is sparse. First I check is the county's page on FamilySearch.org. The wiki on Family Search can be an invaluable resource when it comes to local information, but like any wiki, the results are hit and miss. Since I was recently researching in Augusta County, Virginia, I am going to use that as my example. The Family Search wiki page gives me a brief history of the county along with notes and links about collections that are available online for the county. ((Wherever possible, I like to capture my own images of documents housed at a courthouse even if they are available online because I can use my images without restriction. Documents accessed through online repositories often have restrictions on use. While they are wonderfully accessible, if I want to share a document online I may not be able to if the repository's TOS prohibit it.))

Just under the table of contents, there is a chart showing the dates for which each type of record is available and a link to the county's website. Also listed are the courthouse address and the phone number. If you aren't familiar with the area, you can use this information to check out parking availability. Have small bills and change for meters and parking garages -- just this trip I had to make an out of the way trip to an ATM due to lack of cash for parking.

First Things First: Rules

While courthouses are repositories of documents going back hundreds of years, they are also government buildings full of present day activity. Each locality has different restrictions, but you can expect some combination of metal detectors, searches, and restricted items. Unfortunately, cell phones and cameras are often on the restricted list. Call ahead so that you know exactly what to expect when you arrive. It's no fun to have to trudge back to a parking garage because you tried to get in with your cell phone and got stopped at the door. When I traveled to Georgia for research, the courthouse had a no cell phone rule but was amenable to allowing them into the records room. Some allow cameras but not cell phones, some allow some types of scanners, while some allow virtually nothing but pen and paper for note taking. Ask first so there are no surprises.

Where To Look: Indices

My first courthouse research trip. I love courthouse record rooms even more than libraries.

Most records are stored in large record books like the ones on the wall behind me in the photo to the left. Each set of records will have an index, which is how you will find the specific records you are looking for. The index may be in the front of the book for small collections, while large collections might have several indices in large books divided by time period. The index will be sorted by letter of the alphabet, but the names will usually not be alphabetical within the letter, since they are added to the index as records are filed.

In some cases wills are in their original loose format in a vault, which is a walk-in room similar to a bank vault. It is usually open to the record room but the door can be sealed to protect the records. In this instance, the wills were transcribed contemporaneously by the clerk into will books, and there were 4 will index books covering the period from the early 18th century to the 20th century.

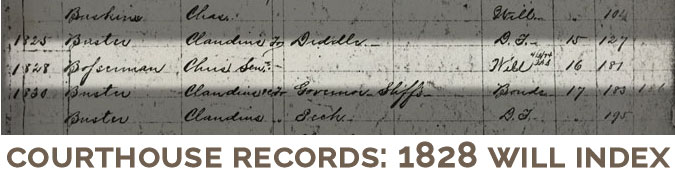

The ancestor I was researching, Christian Bosserman, Sr., died in the early 19th century, so I looked in Will Index 1, which covered the earliest years of the county. I looked under the B's and found the listing below. Notice how the old handwriting differentiates the double s by making the first one larger, making it look similar to an f. Spelling conventions were not uniform until the 20th century, so look for various spellings for the same person. I have seen Bosserman spelled Boserman and Bauserman, while another family name is spelled Bowers and Bauers.

The listing above gives the information I need to find the will: the date that the will was recorded (1828), last name (Bosserman), first name(Chris. Snr.), other parties involved (none), kind of listing (will), book number (Book 16), and page number (pg. 181).

You might wonder why a will index indicates what kind of listing it is, but will books contain more than just wills. Property listings for the deceased, appointment of executors, appointment of guardians for disbursing funds to minors, settlements, and more are found in the will books. This listing indicates that the will of Christian Bosserman, Sr. was filed in 1828, and I will find it on pg. 181 of Book 16. The correct book is easy to find because they are clearly marked and are filed numerically by category.

Pulling the Records: Record Books

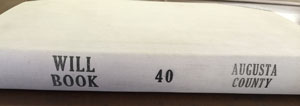

Record books are clearly marked numerically

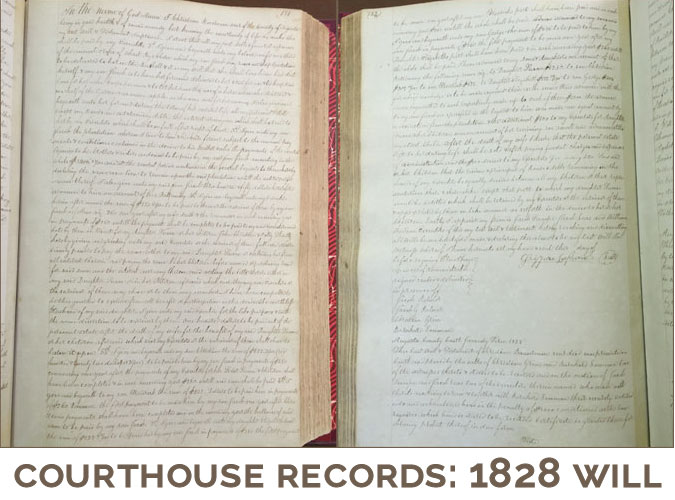

Looking along the wall where the will books are filed numerically, it is easy to find Will Book 16. The pages, although not the original will in the ancestor's handwriting, were transcribed at the time the will was filed and the pages are old and fragile. Carefully turning to page 181 takes me to the will itself.

Although it's tempting to sit and read at this point, usually time is limited so I capture the images and move on. I find it easiest to make a list from the indices of all of the documents I want to view, then use that list to pull and photograph each document before moving on to the next one. Working this way I can maximize my time spent in the records room and sort everything out when I leave. Later, I transfer the images to my computer and rename them according to what they are. The images above are named as follows:

BOSSERMAN-christian-sr-will-1828-augusta-va-bk-16-pg-181.jpg

BOSSERMAN-christian-sr-will-1828-augusta-va-bk-16-pg-182.jpg

The folder for the images contains the name of the repository and the date of the visit, so I have all of the information I need to create an complete citation.

Looking for birth, marriage, and death records is very similar to wills in that you usually look at the index first, then go to the book and page. As I mentioned, some small collections will have the index in the front of the book, so if you don't see a separate index book look there.

Courthouse Genealogy Research: Things to Keep in Mind

Boundary changes. County and city boundaries changed over time, and you need to look at the courthouse for the location that was in existence at the time of the record. Augusta County, Virginia was at one time the most western county in Virginia and extended for hundreds of miles to the west, including areas that are now in West Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, and Ohio. Property deeds for an ancestor that never physically changed location could potentially be in 2 or even 3 counties as boundaries changed over the years. Maps that show county boundary changes are available for every state on MapsofUS.org (scroll about halfway down the page and play the animation to see the changes; a list of states is in the left sidebar).

Civil vs. Criminal. If you are looking for court cases, civil and criminal cases may be filed in different locations. A civil case such as a lawsuit might be filed in a different repository than a criminal case such as a murder trial. Check with the courthouse for more information.

City vs. County. Different states treat localities differently, so be sure you are searching in the right courthouse. In Virginia, cities are independent localities and are not part of a county. As such, they have their own courthouses and all records for the city are separate from the county. Understand the organization of the state's government before assuming that you are looking in the correct place.

State Archives. In some cases certain records are held by the state as well as the county. Typically local records will pre-date state records because many counties kept BMD records before it was required by the state. It depends on the locality which records are available.

Have a question? Let me know and I'll do my best to answer it below. I hope this takes some of the mystery out of how to obtain records from a courthouse. They are my favorite repository, and I hope you find them to be a rich resource for your research.

Leave a Reply